The first Brazilian Constitution turns 200 years old in 2024. The text went down in history as "The Granted," since it was imposed by Emperor Dom Pedro I, who subsequently ordered the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, preventing the political opposition from acting.

The Constitution was also considered "granted" because, following the example of what had been happening in other spheres, it bypassed the population that had fought for political emancipation in 1822.

Brazilians were then socialized by a history of colonial, white, male, European origin, mostly tied to the local elites. In this history, there was almost no space for a large part of the national population—constituted by Black, indigenous people, and women—despite many of them having taken up arms to defend the country. On the other hand, Brazilian art history itself remained marked by this same type of dominant discourse and representation.

On that account, this exhibition aims to pay homage to artists who have long been invisibilized and to bring Afro-Brazilian and indigenous art, including a significant presence of women artists, to an iconic modernist house designed and decorated by the Brazil-based Polish architect and designer Jorge Zalszupin. The exhibition also references and quotes the artworks and furniture originally exhibited there.

Zalszupin lived at this address for 60 years and filled the space with objects of his taste and preference. The result is welcoming living rooms, bedrooms, and bathrooms of unique style, an eating area that breathes conviviality, and a garden that overflows into the house, making it difficult to separate the inside from the outside—the external from the internal.

The city has grown up around the house. Right in front of it, in the same square, São José Church brings crowds of churchgoers to the streets on festive days. Nearby are the busy Faria Lima Avenue and Gabriel Monteiro da Silva Avenue, two fast-paced urban thoroughfares in a São Paulo that never stops.

Meanwhile, the house, hiding in its details of shy and modest beauty, is nearly engulfed in this neighborhood of imposing mansions. It has remained there as if lost or protected by time. Designed in 1960, it features elements of Brazilian Modernism combined with influences the architect brought from Europe, especially Denmark.

After Zalszupin died in 2020, the house's structure remained basically intact. We still can see a balanced exchange between the rustic ceramic floor and the rough walls, a stone surface in dialogue with the jacaranda steps in the floating staircase, colorful glasses in the windows competing with the cold concrete, and a wooden ceiling making the monumental seem cozy.

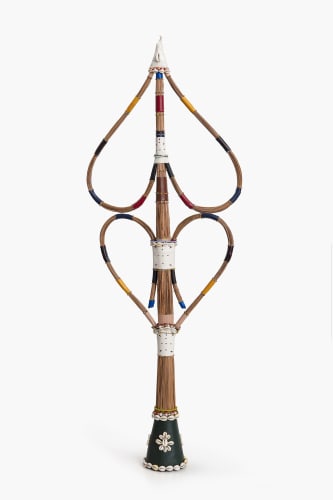

Inspired by this modernist space, I propose to temporarily decorate the house with the "other modernisms" of Afro-Brazilian and indigenous origins. In this celebration of sorts, the roughness of the concrete will compete for space with the strong lines of the Orixas art; the stones will contrast with the ceramic, clay, or bronze sculptures; and straight-line shapes will be in conversation with the indigenous art motifs and their divinities.

The goal is to bring tradition and the contemporary into dialogue, moving away from the classifications of our still Eurocentric artistic canon, which has dismissed as "craft" or "popular and naïve art" a whole range of works bursting with Brazilianness, and challenging the established notions of Modernism and modernity.

Metalinguistically, the exhibition also intends to update the original house decoration, whose vibrant elements—paintings, furniture, sculptures, birdcages, ex-votos, rugs, books—are interwoven with the very intimacy of the family.

The Right to Memory thus seeks to translate into this privileged space—a true gem of Brazilian Modernism—a history that has never ceased to happen but had no place for a long time. Since this history has imposed itself in silence, it is not a matter of including these artists in Modernism, but rather of opening the door to other, dissident Modernisms.

This exhibition aims to "repair"—in the sense of observing and recovering rights—as much as to "occupy," underlining the meaning of cultural and symbolic taking. There are many stories and ways of claiming rights.

Lilia Moritz Schwarcz